In the climate movement’s ongoing efforts to cut off the financing of the fossil fuel industry, perhaps no culprit has loomed as large as the big banks. For nearly a decade, organizers have been naming and shaming the banks that prop up the oil, gas and coal industries, identifying them as key drivers of climate chaos.

There’s a simple reason why banks have been such a big focus: they profit from providing a vital financial lifeline to the fossil fuel industry, keeping it in business and even expanding while it spouts carbon pollution into the atmosphere and dangerous chemicals into frontline communities.

Specifically, banks supply fossil fuel companies with the cash, credit, cover and counseling to sustain and grow their operations. Banks directly lend huge amounts of money to fossil fuel companies through term loans and credit facilities that those companies can draw on to cover their business costs, whether that’s building a new pipeline or developing a new oilfield. They provide crucial intermediary services, such as underwriting new company stock and bond issuances. Banks also rake in millions for facilitating mergers and acquisitions within the fossil fuel industry.

In addition to being key players in the daily reproduction of global fossil capitalism, banks are extremely powerful actors within — and the financial beating heart of — the larger corporate power structure. They are run by influential and lavishly-paid executives, boards that are intertwined with broader networks of corporate power, and well-connected armies of lobbyists. The imprint of banks is nearly everywhere: from our personal savings accounts, to the names of sports stadiums, to the sponsors of local community events, to the boards of police foundations. The biggest banks have a close and cozy relationship with the federal government, with a steady revolving door between the industry and regulatory agencies. Especially in times of crisis, banks and their executives become virtual advisors to top U.S. leaders.

While pushing banks to cut off funding for climate destruction remains a daunting challenge, they do have some vulnerabilities. Many banks are consumer-facing, with tens of millions of ordinary customers who care about the fate of the planet and its people. They are subject to government oversight and regulation, including around climate, and this can be deepened by activist pressure and further policy changes. They have executives and directors with public profiles who care about their reputations. All this opens up points of leverage for organizers to campaign around as they continue to try to drive a wedge between banks and the fossil fuel industry.

How do banks finance and profit from climate chaos?

The ways that banks prop up and profit from the fossil fuel industry are very concrete and, while complex in their details, are easy to grasp in their basic essence. These include:

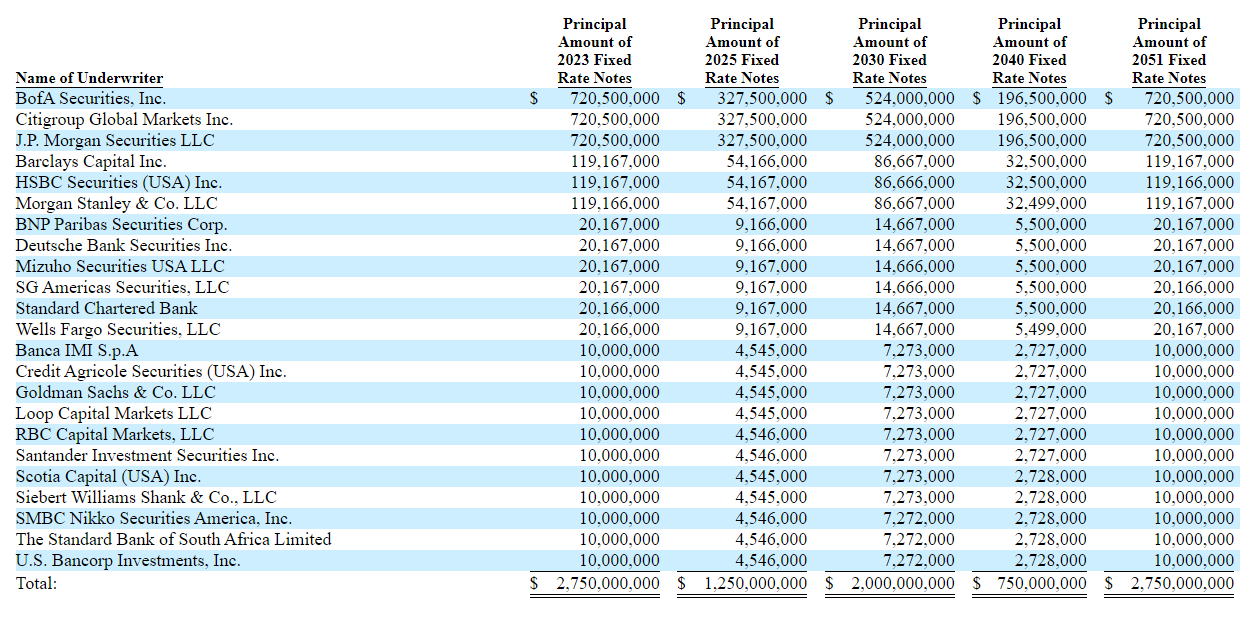

- Underwriting bonds: Banks help oil, gas and coal companies raise huge amounts of cash by underwriting their corporate bonds (also called notes). Bonds and notes are forms of debt that companies can issue to buyers so that they can raise money to finance their business. For example, in 2020, a consortium of 23 banks led by Bank of America, Citi, and JPMorgan agreed to facilitate $9.5 billion in corporate notes for ExxonMobil notes. Under the agreement, the banks agreed to each purchase and then sell discrete chunks of the total $9.5 billion. Exxon stated it would use the proceeds for “general corporate purposes, including, but not limited to, refinancing a portion of our existing commercial paper borrowings, funding for working capital, acquisitions, capital expenditures and other business opportunities.” For their part, the banks profit in the millions from all this through fees they charge.

The banks underwriting $9.5 billion in ExxonMobil corporate bonds (ExxonMobil SEC filing, April 2020)

- Credit facilities and term loans: A main way that banks prop up fossil fuel operations is through credit facilities, which is another way of saying that banks make a certain amount of money available for oil, gas and coal companies to draw on and borrow if they wish. The companies can then use these funds for their operations, expansion and other costs. For example, eighteen banks led by Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase provided a $3.25 billion credit facility to Atlantic Coast Pipeline LLC, which was overseeing the construction of the now-defunct Atlantic Coast Pipeline (the other banks committed to the credit facility were the Bank of Nova Scotia, Barclays, BB&T, CoBank, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, KeyBank, Mizuho, MUFG, National Bank of Canada, PNC Bank, Royal Bank of Canada, Sumitomo Mitsui, Suntrust, TD and Wells Fargo). Lynn Good, the CEO of Duke Energy, a 47% owner of the pipeline, said the credit facility would be used to “fund approximately half of the pipeline construction costs” and that “the project has borrowed $570 million against the facility to cover costs incurred to date.” Fossil fuel companies can also take out “term loans” with banks which, unlike credit facilities, have more specific loan amounts and payback dates. Here, for example, is a filing where refining giant Phillips 66 refers to a $450 million term loan it took out. Banks profit from all these loans primarily from interest payments when the loan is paid back.

- Advising on mergers and acquisitions: Fossil fuel companies sometimes acquire one another and merge, and they need banks to advise, guide financial transactions and provide bridge loans to facilitate all this. For example, one of the biggest oil mergers in recent decades was Occidental’s acquisition of Anadarko. The Financial Times reported that Bank of America and Citi were advising Occidental on the merger and could rake in $170 million in fees to split with Anadarko’s advisors. More than $100 million more could be earned by the banks through financing the transaction.

Through mechanisms and relationships like these, banks play an indispensable role in the operation and expansion of the fossil fuel industry that is driving climate catastrophe.

Which banks finance climate chaos?

Every year a group of climate organizations release a fossil fuel finance report that documents the top banks that are financing climate chaos. The 2023 report looks at the top 60 global banks by assets and ranks them according to how much they finance the fossil fuel industry through lending and underwriting. The report finds that, in 2022 alone, these banks provided $673 billion to fossil fuel companies. From 2016 — the year of the Paris Agreement — to 2022, the top 60 banks have provided an astounding $5.5 trillion in financing to fossil fuel companies.

The top four financiers of fossil fuels from 2016 to 2022 are all powerhouse U.S. banks: JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America. Together, during those years, these four banks alone have financed the industry to the tune of a whopping $1.366 trillion — a full quarter of all financing to the fossil fuel industry among the top 60 banks.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total | |

| JPMorgan | $65.357 B | $72.817 B | $69.365 B | $66.134 B | $53.983 B | $67.258 B | $39.240 B | $434.154 B |

| Citi | $45.691 B | $50.239 B | $49.734 B | $54.721 B | $51.635 B | $46.945 B | $33.943 B | $332.907 B |

| Wells Fargo | $37.581 B | $55.955 B | $62.524 B | $45.533 B | $27.954 B | $49.755 B | $38.899 B | $318.200 B |

| BoA | $39.157 B | $38.399 B | $35.148 B | $50.188 B | $45.454 B | $35.916 B | $36.967 B | $281.230 B |

It should be added that these four banks are also the top four holders of U.S. domestic deposits, meaning they’re financing fossil fuels with the cash deposits of regular working people who overwhelmingly support action to mitigate climate change.

The report also breaks down financing in specific areas. JPMorgan and Citi are far and away the top financiers among the top 100 key oil, gas and coal companies expanding fossil fuels from 2016 to 2022. New Jersey-based TD bank is the top financier of the top 27 top tar sands companies and six key tar sands pipeline companies in 2022. JPMorgan has been the top financier of the top 30 Arctic production companies from 2016 to 2022 (Citi is #3 and Bank of America is #7). Wells Fargo has been the top fracking financier from 2016 to 2022, followed by JPMorgan, Citi, and Bank of America.

It’s also worth noting that banks themselves, through their asset management arms, are big stakeholders in fossil fuel companies. For example, JPMorgan Chase owns about 4.9% of Conocophillips and 1.3% of ExxonMobil; Bank of America owns about 1.6% of Chevron and 1.32% of ExxonMobil; Citi owns 2.27% of DCP Midstream and just under one percent of ExxonMobil; Wells Fargo owns 3.66% of Phillips 66 and 0.79% of EOG Resources.

While the big fossil financing banks make a range of climate gestures, from making net-zero declarations that are decades away to sponsoring climate summits, this ultimately amounts to greenwashing when compared to their continuous commitment to funding fossil fuels — for example, by constantly rejecting pro-climate shareholders proposals that will ensure they keep bankrolling climate chaos.

Top shareholders of fossil fuel corporations are the same top shareholders of fossil-financing banks

Moreover, the biggest asset manager owners of fossil fuels — BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street — are also the top shareholders of the major fossil financing banks. For example, the top beneficial owners (with a 5%+ ownership stake) of each of the big four fossil financing banks, as listed in the banks’ most recent proxy statements, include asset management giants BlackRock and Vanguard who, as we’ve shown, are also the top shareholders of publicly-traded fossil fuel companies across the board, while Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway is the top shareholder of Bank of America.

| Vanguard | BlackRock | Berkshire Hathaway | |

| JPMorgan | 9.36% 274,622,643 shares | 6.6% 194,920,731 shares | |

| Bank of America | 7.6% 607,703,467 shares | 5.9% 474,777,122 shares | 12.9% 1,032,852,006 shares |

| Wells Fargo | 8.78% 331,546,750 shares | 7.1% 268,358,243 | |

| Citi | 8.66% 167,689,164 shares | 8.4% 163,468,812 shares |

This means that just two asset management firms (Vanguard and BlackRock) have a 15.96% stake in JPMorgan, a 15.88% stake in Wells Fargo, and a 17.06% stake in Citi, while those two firms plus Buffett’s berkshire Hathaway together have a 26.4% stake in Bank of America.

In essence, the top shareholders of the fossil fuel industry — the big asset managers — are also the top shareholders of the banks that are the top financiers of that same fossil industry industry. All this points to the strategic importance for the climate movement in focusing on the interlocking web of financial actors that prop up and profit from the fossil fuel industry.

The Big Banks’ lobbying operation

While individual banks have their own huge lobbying operations — JPMorgan alone spent nearly $4 million on federal lobbying in 2022 — the industry as a whole relies on trade groups to advance their interests among elected officials and regulators.

Key banking industry lobbying groups include the American Bankers Association, Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, and the Bank Policy Institute, the latter of which is governed by major bank CEOs (JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon is the Chairman) and spent $2.47 million on federal lobbying in 2022.

Other bank lobbying groups include the Investment Company Institute — which represents big asset managers, but also banks with asset management wings — and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which broadly represents the interests of the U.S. corporate class and whose board includes several banks and financial groups. Bank of America, Barclays, BlackRock, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, TD Bank, and Wells Fargo are all members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

While virtually every bank has a “sustainability” page on its website, lobbying efforts by banks and their industry groups help prop up the fossil fuel industry and help maintain the industry’s bankrolling of climate destruction. A 2022 report by Influence Map report documented the extensive lobbying efforts by the banking industry against stronger climate regulation.

For example the report notes that in 2021 industry associations like the American Bankers Association pushed to remove “explicit references” to “ESG factors” when consulted by the U.S. Department of Labor’s on its Prudence and Loyalty in Selecting Plan Investments and Exercising Shareholder Rights, which sets guidelines around fiduciary duty for retirement accounts, including around climate issues and climate risk. The industry groups also “opposed mandatory ESG considerations in the investment process.”

The report also notes, for example, that in 2021 the Bank Policy Institute advocated to the SEC “for a gradual and flexible approach” to climate change disclosures and that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s “sustained opposition to regulated corporate climate disclosure.”

Executive and board power: The case of JPMorgan Chase

To understand the power and influence of the banking sector, it’s instructive to look at its most powerful member, and the world’s top financier of fossil fuels: JPMorgan Chase.

JPMorgan is a banking behemoth with $3.7 trillion in assets and a quarter-million employees globally. Its size and power is the result of over two centuries of expansion, mergers and consolidation. The bank has numerous arms: commercial banking, financial services, asset management, and more. In 2022 it raked in a whopping $35.6 billion in profits.

In recent decades, JPMorgan has risen above even the other mega-banks as the U.S.’s banking hegemon. In 1991, its market share was 1.5%, versus 14.4% today — a ten-fold increase in its domination of the banking sector. What BlackRock is to asset management, in terms of its centrality and power within that sector, JPMorgan is to banking and financial services.

This centrality was recently seen, for example, in JPMorgan’s go-to role in acquiring the huge failing U.S. banks SVB and First Republic. In seeking help with the latter, the Financial Times reports that JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon was the “first port of call” for Treasury secretary Janet Yellen.

In other words, like BlackRock, JPMorgan isn’t just a bank — it’s a structure that the entire financial system runs through and depends on. Economic historian Adam Tooze said that JPMorgan’s savior role in the recent bank collapses moved it “from being just one of America’s big banks to being the American bank. It is the central player in the system” and a “universal player, a key player, in investment banking, market making, in asset management…”

At the helm of this financial goliath is one of the most influential CEOs in the world: Jamie Dimon.

Dimon, the longest-serving bank leader, is a billionaire who raked in nearly $100 million in total cash and stock compensation from 2020 to 2002. As of May 12, 2023, he owned, directly and indirectly, 8,631,515 shares of JPMorgan stock, worth over $1.1 billion. While Dimon is no Jeff Bezos, he does flaunt his wealth and status — notoriously, in tone-deaf and ostentatious family Christmas cards he sent out in 2013.

Nor is Dimon a purely financial bigwig. À la union-buster-in-chief Howard Schultz, he fashions himself something of a political leader, and rumors have circulated for years over potential Dimon presidential runs.

Beyond the power he wields at the helm of the core U.S. bank, he’s also extremely well-networked. Among other ties, Dimon is a director of the Business Roundtable, chair of the Bank Policy Institute, an executive committee member of the Partnership for New York City, and, according to his company bio, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a board member of Harvard Business School.

Despite green lip service, Dimon is unabashedly pro-fossil fuels.

In August 2022 he lamented to clients: “Why can’t we get it through our thick skulls” that America should “boost more oil and gas?” (which he said would be good for the climate). In September 2022 he pleaded to Congress that the U.S. needed to invest in more fossil fuels and said if his banks stopped funding new fossil fuel products it would “be the road to hell for America.” In January 2023 he told Fox News that “we need pipelines” and “permits.”

The coalition Stop The Money Pipeline has gone so far as to state that at “various points over the past few years,” Dimon “has essentially transformed into a fossil fuel lobbyist” — for example, when JPMorgan secretly emailed the Trump administration to bail out the oil and gas industry during the onset of the pandemic.

JPMorgan’s fossil financing is not only upheld by Jamie Dimon, but also by his boss: JPMorgan’s Board of Directors, the entity that governs the company and has the power to hire and fire top executives.

Simply put, JPMorgan’s board is a who’s-who of huge corporate bigwigs that represents key industries from insurance to telecoms, retail to healthcare, defense to manufacturing. In turn, the company’s directors — and the affiliations they carry — are all part of the wider web of power behind the bank that upholds its primary role in propping up climate chaos.

Corporations represented on JPMorgan’s board, as measured by the current and past affiliations of board members, include: NBCUniversal, GEICO, Amazon, KPMG, United Health, Walmart, Alcoa, Johnson & Johnson, Starbucks, General Electric, IBM and more. Ties like these reflect how JPMorgan is directly situated at the center of the U.S. economy and its major industries that drive extraction and exploitation.

Strikingly, Berkshire Hathaway, the investment conglomerate owned by Warren Buffett, the world’s fifth-richest person (net with: $106 billion), has two significant ties to JPMorgan’s board. Berkshire Hathaway, it should be noted, is bullish on fossil fuels and has an energy and utility arm that has been historically bad on climate issues.

Lobbying powerhouses and think tanks like the Business Roundtable and Council on Foreign Relations, as well as major universities like Northwestern and University of Pennsylvania, are tied to JPMorgan’s board through network interlocks.

One JPMorgan director, Mellody Hobson, is a big business celebrity — a friend of Oprah and the Obamas who is married to billionaire Star Wars creator George Lucas. Hobson also happens to be the Starbucks board chair, helping to oversee a historic union-busting campaign.

Keeping the pressure up on Big Banks

With the persistent opposition from banks to more aggressive climate action and to defunding fossil fuels, the outlook remains challenging for climate and environmental justice organizers in trying to end banks’ oil, gas and coal financing. Nevertheless, banks remain a crucial and strategic focus for the climate movement for a number of reasons.

Foremost, as a campaign target they are more vulnerable than the fossil fuel industry itself. ExxonMobil, for example, is existentially dedicated to oil and gas production, which is its core business. No amount of protesting at, say, Exxon’s corporate headquarters will change that. But Bank of America, on the other hand, is a consumer-facing brand that does the overwhelming majority of its business outside of the fossil fuel sector. Whereas Exxon — or Chevron, or ConocoPhillips, and so on — can’t abandon fossil fuels without becoming an entirely different company, Bank of America — or JPMorgan, or Wells Fargo, and so on — could move away from fossil fuels and continue operating more or less normally.

Because banks have a lot less to lose than fossil fuel companies in ditching oil and gas, and because they do business with millions of consumers and thousands of other companies that care deeply about climate issues, they may be easier to move. On top of that, there’s evidence that banks face significant financial risk from the climate catastrophe and from business with fossil fuels — a point that activists and concerned shareholders can continue to agitate around.

Moreover, the strategy of going after banks has a proven record of success. To take one example: in 2019, due to pressure from campaigns like the Families Belong Together coalition, organizers succeeded in pushing banks to halt almost all of their term loans and lines of credit to the private prison industry. And even though it didn’t stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, the exposure of the banks that were financing the project expanded the area of protest for organizers and educated thousands on the role of Wall Street in the buildout of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Right now, numerous organizations and campaigns are working to push banks to break with fossil fuels, For example, the Stop the Money Pipeline coalition, made up over over 200 organizations, has ongoing campaigns focused on banks and their ties to the fossil fuel industry, and its member groups are continuously engaged in protest actions, shareholder activism, new campaigns, and other work aimed at driving the wedge between banks and the fossil fuel industry.

While a challenging task, activists must keep up the fight to pressure banks — who after all, remain strategic climate targets with their own vulnerabilities and fissures that campaigns can organize around — to halt its role in climate destruction.